From the East, the 1st Battalion Munster Fusiliers left Rangoon in December 1914. From the West, two young men in their twenties — my father Robert Jordan and his brother Peter — left New York to join up with them.

The connection between these two events goes back to my Grandfather, John Jordan. Born in 1836 in County Limerick, Ireland, John Jordan lived in interesting times. He was a child of nine when the Irish Potato Famine began, but survived when millions died. Many are the tales of horror from those years but, for some reason, one small story stays in my mind. The Relieving Officer from John’s town was passing a churchyard at dusk and saw a figure among the graves. Fearing some desecration, he crept in and found an emaciated woman. “What are you doing here'” he asked. “Oh sir”, said she, “my children are starving and the nettles do be growing here so nicely, I pick them at night unnoticed.”

The connection between these two events goes back to my Grandfather, John Jordan. Born in 1836 in County Limerick, Ireland, John Jordan lived in interesting times. He was a child of nine when the Irish Potato Famine began, but survived when millions died. Many are the tales of horror from those years but, for some reason, one small story stays in my mind. The Relieving Officer from John’s town was passing a churchyard at dusk and saw a figure among the graves. Fearing some desecration, he crept in and found an emaciated woman. “What are you doing here'” he asked. “Oh sir”, said she, “my children are starving and the nettles do be growing here so nicely, I pick them at night unnoticed.”

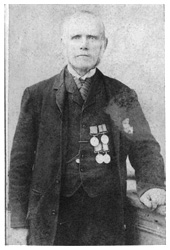

At the age of 17 years and 10 months, John Jordan enlisted with the 57th regiment of Foot at Tralee, and saw service with them in the Crimea, where he was present to observe the Charge of the Light Brigade and to take part in the capture of Sevastopol. Later, he was in India at the time of the Indian Mutiny and in New Zealand for the Maori Wars.

Marrying late, he still managed to produce 19 children with two wives. Leaving the Army and returning to Ireland, he was recruiting Sergeant for the Munsters. On his death, in 1906, the family emigrated, two by two, to America.

Many of the soldiers returning from Burma would have been recruited by him, as were at least four of his own sons, including the two now rejoining their old regiment.

It puzzles me to know what motivated them to do so. I suspect that, if I had been safely settled in America, I would have needed some persuasion before putting my head in the fire. There is irony in the affair because, sixty years before, John Jordan had passed through the Dardanelles to the Crimea to help the Turks and prevent the Russians getting access to the Mediterranean. Now, two of his sons would be going there to fight the Turks in order to preserve Russian access.

There is a photograph of the Munsters on Pool Meadow, waiting to be billeted around the city, when they arrived in Coventry on 11th January 1915. Truth to tell, they look a pretty raggedy lot, with a strange mixture of uniforms: some in tropical kit, with pith helmets; some in new uniforms; a few looking particularly bedraggled. I suspect that the latter might be survivors from the sister battalion, 2nd Munsters, which had been virtually wiped out when forming the rearguard at Etreux in the Retreat from Mons.

There is a photograph of the Munsters on Pool Meadow, waiting to be billeted around the city, when they arrived in Coventry on 11th January 1915. Truth to tell, they look a pretty raggedy lot, with a strange mixture of uniforms: some in tropical kit, with pith helmets; some in new uniforms; a few looking particularly bedraggled. I suspect that the latter might be survivors from the sister battalion, 2nd Munsters, which had been virtually wiped out when forming the rearguard at Etreux in the Retreat from Mons.

On the very day the picture was taken, Admiral Cardan presented his plan for the naval assault on the Dardanelles to the War Cabinet. Already, fatal flaws in the higher strategy were beginning to show: the Navy assumed that this would be no more than a demonstration that could be broken off at any time, leaving the Army to finish the job; the Army expected only to be a reserve to assist a Naval operation.

The soldiers in Coventry, of course, knew nothing of the rhetoric and delusions of politicians and the higher military in London. There, the determined optimism of Churchill confronted the doubtful pessimism, or realism, according to point of view, of Jackie Fisher and the more complex reservations of Kitchener. Churchill said: “what an excellent thing it is to have an optimist at the front.” Prime Minister Asquith said: “Excellent, provided you also have, as we have in Kitchener, a pessimist in the rear.”

Even had they known all, the soldiers would not and could not have done other than they did. For them, one option only, the ageless tactic of the powerless: imitate the action of the ostrich; what cannot be cured must be endured; seek pleasure today, for tomorrow we die. Seek warmth.

All accounts of the Munster’s stay in Coventry agree that they won and warmed the hearts of Coventrians with their humour and geniality. If you have ever visited the West of Ireland, you will recognise this extraordinary warmth and openness. Even seventy years later, elderly Coventrians, writing to the local paper, recalled this. Warmth met warmth.

But, if the people were warm, the climate certainly wasn’t. These troops were transported suddenly from tropical summer to bitterly cold and bleak English January. Their light clothes were not suitable and one account says they were dropping in the street with ague. One reputed remedy was the cheap whiskey of those days with, at times, predictably unfortunate results. One story describes them as big, rough fellows, always ready for a scrap, and tells of a particular incident when a drunken soldier insulted a lady in a chip shop on the Radford Road. An officer was called to investigate.

“Paddy”, he said, “You are a damned nuisance and a sloppy soldier and this time you are going to get it.” Then he knocked the soldier into the gutter with a left and a right. Two soldiers were then ordered to frogmarch the offender back to barracks.

Other sources of warmth were sought. Most of the troops were billeted in Earlsdon or Chapelfields and practised their shooting at the Butts. Now, these were young men, with young men’s urgencies. Coventry was not short of attractive young women, many working nearby at Rotherhams watch factory. Unsurprisingly, there were mutual attractions. Some later resulted in marriages. William (Paddy) Long, one of two brothers from Glanworth in County Cork, was billeted with the Allen family in Lord St., Chapelfields and soon began courting the eldest of their three daughters. He came back from the War to marry her and raise a family in Coventry, working for years on the trams.

My father met my mother, Elsie Flemming then. She was just convalescing from a cycling accident.

Not all waited to return from the War. The Graphic ran a picture story, reporting the happy occasion when Lieutenant Sullivan married Miss Maud Bates at St. Osburgs.

The Coventry Graphic ran regular stories on the Munsters. In December, the main topic had been ‘Spy Scares’. By the middle of January, ‘Khaki Coventry’ was the new topic of interest. There were pictures of training in the lanes of Warwickshire and of soldiers helping gardeners set potatoes as well as coverage of concerts and sporting competitions.

One item caught my attention. The Munsters dug a deep depression “more than a mere trench” at the Kenilworth Road end of Earlsdon Avenue. They were trying out a new entrenching tool. The depression, like a small valley, can still be seen. Thirty years later, when I was a boy, trees had grown round it, and it was known as the “Devil’s Dungeon”. Now, it happened that our school cross-country race passed through it and I remember Tom Wyer and myself plotting to take advantage of its cover to make a break from the pack and get a good lead. It worked. Tom was first that year, and I was third. I didn’t know then that my father had anything to do with the feature.

Soon enough, the weeks in Coventry drew to a close. By the end of February, there was a slight note of premonition about the Graphic: “Our military guests are expected to depart for their war stations soon.” There was a flurry of presentations from the Citizens of Coventry and warm words of appreciation from their Irish guests.

The battalion was presented with a mascot , an English bull-terrier called ‘Buller’. He was given a khaki coat for weekdays and a braided emerald green one for Sundays. Buller was put on the battalion roll and drew billet money of eight shillings and nine pence — half that of a soldier.

The Coventry Irish Club presented a flag with the emblem Erin go Bragh (Ireland for Ever), given with the hope that it would inspire them in the stirring events before them. Sergeant O’Donaghue gave thanks and hoped to carry the flag to Berlin.

Beneath the air of buoyant joviality, there must have lurked apprehension. Ten-year-old Elsie, from the fruit shop in Earlsdon Street was sharp enough to notice this. Seventy years later, she still remembered when the soldiers were issued with new boots and Martin O’Malley said quietly: “I expect they are for my grave.”

Such thoughts have no place in patriotic fervour. The City presented the battalion with an illuminated scroll of thanks and the soldiers marched through the streets of Coventry with the band playing. Then they marched out to Stretton to be reviewed by their King before departing for whatever fate awaited.

Before departure, my father marched up to the Nursing Home where my mother was convalescing. He charmed the stern matron to let him see Elsie. He asked her to wait for him. She said she would not promise, but said she would be straight with him and let him know if she met someone else.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.