A Story About Rob’s Dad

My dad died two years ago today. To mark the anniversary, here’s a story. The story features several of my favourite things, including: mathematical analysis, football pools, Butlins holidays, retro geekery, repair, and of course my dad.

My dad died two years ago today. To mark the anniversary, here’s a story. The story features several of my favourite things, including: mathematical analysis, football pools, Butlins holidays, retro geekery, repair, and of course my dad.

The System

If Caroline’s dad and mine are anything to go by, having a clever uncle was a powerful factor in working-class boys escaping pre-war poverty. Peter had his Uncle Reg, who taught him to play chess. My dad had Uncle Arthur. Arthur was a veteran of the Great War, invalided out I think. For a while, our family had his hand-written war diaries, until they were snatched back by another family member, something that upset my dad greatly.

Arthur had introduced my very young dad to The System. For Arthur I think it was horse racing. The two of them would pore over The Sporting Life, analysing the horses’ form, scratching out some calculations to eventually come up with a mathematical assessment of the odds offered. I don’t know how good Arthur’s system was, but it clearly had a profound effect on my dad. As I grew up, he had a System for analysing everything. Sometimes it was the horses, eventually, when he had a little cash to invest, it was the stock market. He even applied it to his work, assessing kids’ reading ability. But in the early 1970s it was the football pools.

The Football Pools

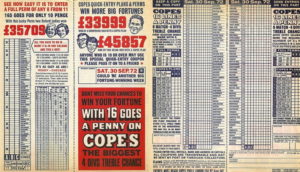

For the uninitiated, football pools were a hugely popular form of betting in mid-20th century England. The art was to predict which of the 46 Football League matches on any given Saturday would be score draws. Eight correct guesses would win you a First Dividend, and a share of the pool. It was so popular that armies of agents would walk door-to-door on a Thursday evening, collecting the completed coupons and stakes, and pocketing a 12.5% fee for their trouble. It strikes me that the agents probably had the best of this. But my dad reckoned he had an edge. The System, as I first remember it, involved an array of index cards, with years of match scores written on each card. Rothman’s Football Yearbook was an essential part of The System, as it detailed all the relevant results from previous seasons. Each week, referencing the data on the cards, Dad would come up with an estimate of the likelihood that each match would be a score draw, and put his crosses on the coupon accordingly. “Come up with an estimate” rather glosses over the detail, which involved a great deal of calculation. Surprisingly, Dad had no higher mathematical education at all, but he was self-taught in some pretty chunky statistical techniques.

For the uninitiated, football pools were a hugely popular form of betting in mid-20th century England. The art was to predict which of the 46 Football League matches on any given Saturday would be score draws. Eight correct guesses would win you a First Dividend, and a share of the pool. It was so popular that armies of agents would walk door-to-door on a Thursday evening, collecting the completed coupons and stakes, and pocketing a 12.5% fee for their trouble. It strikes me that the agents probably had the best of this. But my dad reckoned he had an edge. The System, as I first remember it, involved an array of index cards, with years of match scores written on each card. Rothman’s Football Yearbook was an essential part of The System, as it detailed all the relevant results from previous seasons. Each week, referencing the data on the cards, Dad would come up with an estimate of the likelihood that each match would be a score draw, and put his crosses on the coupon accordingly. “Come up with an estimate” rather glosses over the detail, which involved a great deal of calculation. Surprisingly, Dad had no higher mathematical education at all, but he was self-taught in some pretty chunky statistical techniques.

Calculating The System by hand was intensely time-consuming and error-prone, so he bought a hand-cranked, mechanical calculator. Realise, in the days before electronic calculators, it was a choice between a slide rule (slow and giving only approximate answers) and one of these amazing contraptions. It required a kind of physical long multiplication, with each digit being processed by an appropriate number of rotations of the handle. [I’ve only just learned that it was a Marchant XL, made between 1923 and 1936, see it on video here.] He must have developed a strong right arm! I don’t remember how long the mechanical calculator was in service, but with the advent of desktop electronic adding machines, it was eventually replaced with a very basic electronic model.

Calculating The System by hand was intensely time-consuming and error-prone, so he bought a hand-cranked, mechanical calculator. Realise, in the days before electronic calculators, it was a choice between a slide rule (slow and giving only approximate answers) and one of these amazing contraptions. It required a kind of physical long multiplication, with each digit being processed by an appropriate number of rotations of the handle. [I’ve only just learned that it was a Marchant XL, made between 1923 and 1936, see it on video here.] He must have developed a strong right arm! I don’t remember how long the mechanical calculator was in service, but with the advent of desktop electronic adding machines, it was eventually replaced with a very basic electronic model.

On a foggy Saturday night in November 1973, the very first week that the electronic adding machine had been used, we went to the fair on Hearsall Common. It was a typical family outing. I was 10 and my sister Helen was five. Probably, a goldfish was won, to be put in a demijohn, and nurtured for a few months until the inevitable demise occurred and it was flushed down the toilet. We bought a copy of ‘The Pink’, the Saturday evening sports edition of the Coventry Evening Telegraph, and my dad checked the results. Score draws: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7…. 8! A first dividend!! As we walked home, I think Dad was carrying Helen on his shoulders, but was so distracted that he walked under a road sign gantry, clonking her on the head. She wasn’t that badly hurt, at least, not so badly as the time I hurled her out of a push-chair, landing flat on her face on a pavement. I digress…

So, a first dividend! We were in the money! How much money though would depend on how many other punters had first dividends, the pot being divided among all the first dividend winners. Some weeks, there would be only one, and the winnings would be truly life-changing. It took several days for the results to be tabulated and the prizes announced. Around Tuesday of the next week, we found out that there was another winner who had picked nine score draws and therefore won nine shares of the pot. It left my dad with a prize of £1,800; about a year’s salary, a major cause for celebration. We booked a holiday at Butlins, Skegness, for the next summer, which was one of the happiest holidays of my life! There was money for presents for the family, and some to be invested; bring on The Stock Market System!

Then my dad did what any sensible person would do in the circumstances. He discarded the cheap adding machine that had earned its cost many times over in a single week, and immediately bought himself the best electronic calculator known to mankind.

The Calculator

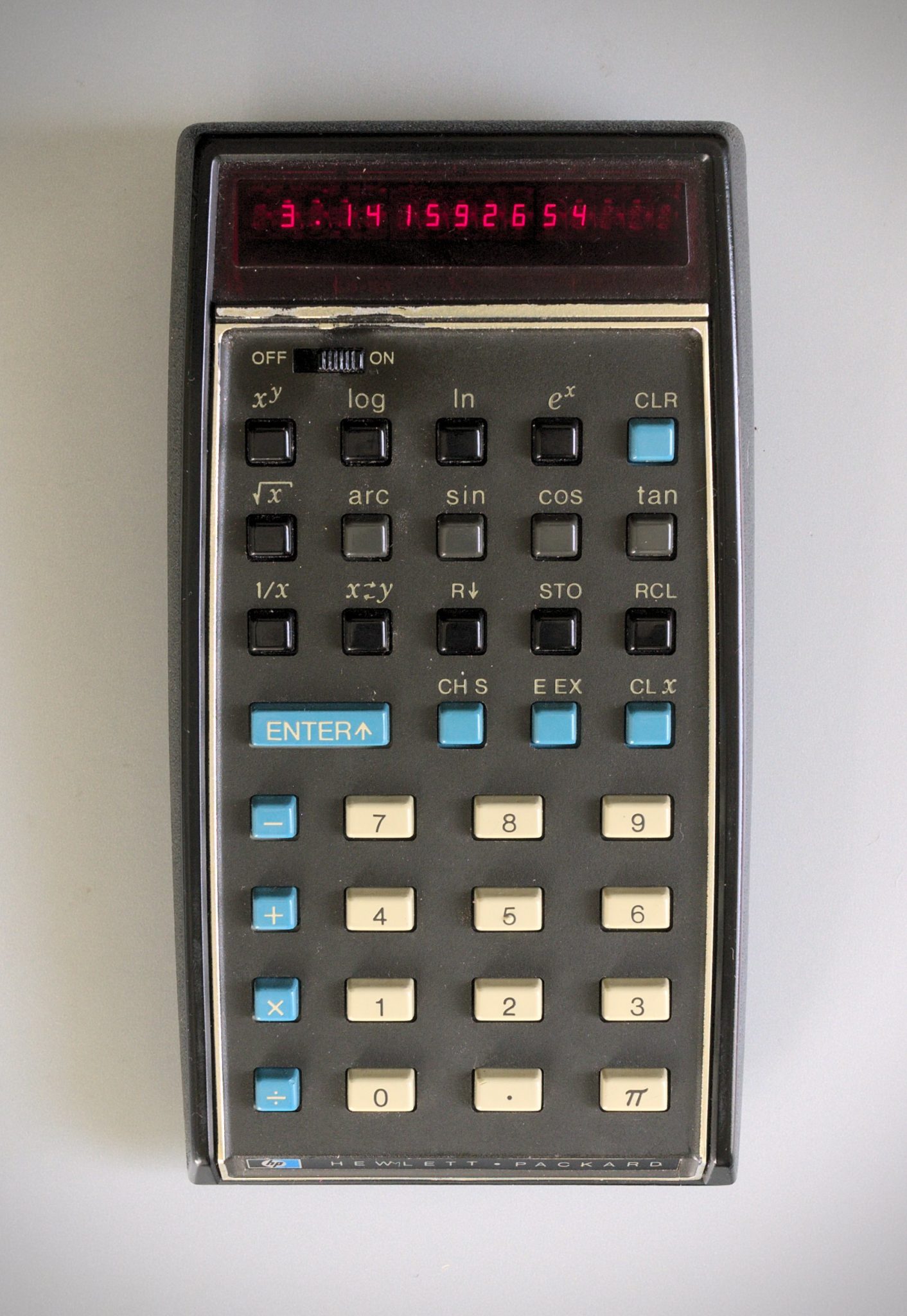

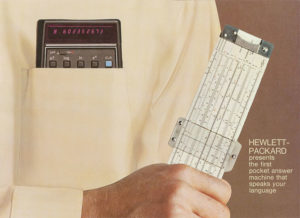

Stanford graduates Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard had started out in the 1930s, in a garage in Palo Alto, California. Silicon Valley as we would now know it, but at that time mostly orchards. Through the 40s, 50s, and 60s, they built up the most prestigious engineering company in the world, designing and manufacturing precision test equipment for laboratories and engineering companies. In 1968, they came up with a new line, the Hewlett Packard 9100A, a scientific calculating machine the size of a large typewriter, and costing $5,000. It might well have been described as the first personal computer, but Hewlett said “If we had called it a computer, it would have been rejected by our customers’ computer gurus because it didn’t look like an IBM.” Instead they called it a calculator.With the new machine launched, Bill Hewlett turned to the engineers responsible for the 9100A, Tom Osborne and Dave Cochrane. Rather than praise, they got a new challenge: “I want it to be a tenth of the volume, ten times as fast and cost a tenth as much.” He wanted a scientific calculator that could fit in an engineer’s shirt pocket, instead of filling up most of the engineer’s desk.

Needless to say, the engineering challenges were enormous, but over a couple of years, Osborne and Cochrane came up with a design. The snag was the project cost; over a million dollars. “That’s when a million dollars was really a million dollars”, said one engineer. HP had poor financial results in 1970, and the outlook for massive, high-risk launches was not good. Ignoring advice from the Stanford Research Institute to cancel the project, Hewlett gave the go-ahead on February 2nd, 1971. The fascinating story of that product development is too long to expand here, but to cut a long story short, the HP-35, the world’s first scientific pocket calculator, was launched in January 1972 at a price of $395.

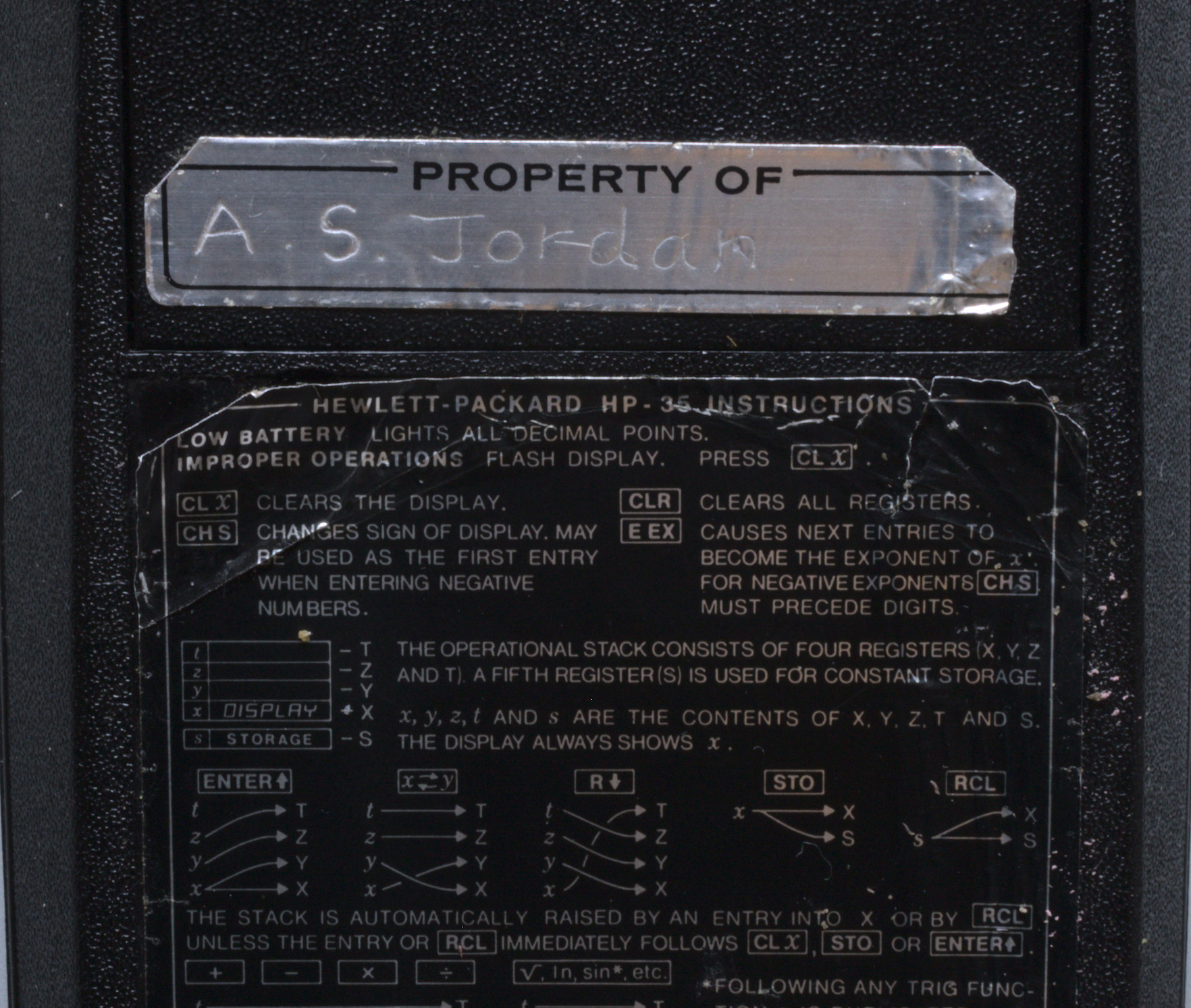

There’s a tale from shortly after the launch that gives a clue to why HP was such an admired company. Two of the calculator’s functions are ln (log natural) and ex. Each is the inverse of the other, so, if you take a number, press ln and then press ex, you should get back the number you first entered. In the course of exhaustive testing, an extremely obscure bug was found. 2.02 ln ex gave the answer 2. Dave Packard called a meeting and asked the team what they were going to do, with more than 25,000 units already in the field. Someone in the crowd said “Don’t tell?” At this Packard snapped his pencil and said: “Who said that? We’re going to tell everyone and offer them a replacement. It would be better to never make a dime of profit than to have a product out there with a problem”. Every one of the calculator’s 768 words of program memory had been filled, so the fix involved not only resolving the incorrect calculation, but finding a way to reduce the space occupied by other functions. Nonetheless, a fix was devised and offered to every owner. Only around 30% took up the offer, many keeping the recall letter as a memento.

There’s a tale from shortly after the launch that gives a clue to why HP was such an admired company. Two of the calculator’s functions are ln (log natural) and ex. Each is the inverse of the other, so, if you take a number, press ln and then press ex, you should get back the number you first entered. In the course of exhaustive testing, an extremely obscure bug was found. 2.02 ln ex gave the answer 2. Dave Packard called a meeting and asked the team what they were going to do, with more than 25,000 units already in the field. Someone in the crowd said “Don’t tell?” At this Packard snapped his pencil and said: “Who said that? We’re going to tell everyone and offer them a replacement. It would be better to never make a dime of profit than to have a product out there with a problem”. Every one of the calculator’s 768 words of program memory had been filled, so the fix involved not only resolving the incorrect calculation, but finding a way to reduce the space occupied by other functions. Nonetheless, a fix was devised and offered to every owner. Only around 30% took up the offer, many keeping the recall letter as a memento.

The HP-35 was a spectacular success. Needing to sell 10,000 to break even, HP sold 100,000 calculators in the first year alone, and 350,000 in the product’s three-year lifetime. Despite ramping up manufacturing, it took 18-months to clear the order backlog. The calculator division became the most important part of HP’s business, delivering more than half of its profits, and relocated to a new campus in Cupertino. There they hired a young engineer to develop calculators; his name was Wozniak and his hobby was building a computer in a garage. Many years later, Wozniak’s partner Steve Jobs acquired the same Cupertino site as Apple’s resplendent headquarters.

I was disappointed to find that the HP-35 didn’t make any moon landings, but it did travel with astronauts on Apollo flights to Skylab in 1973 and 1974. James Burke used to wear one on his belt as he presented the BBC coverage of those space missions.

And my dad bought one for his football pools system.

The Repair

I inherited my dad's HP-35. It was badly damaged by a leaking battery pack somewhere along the line, and failed to come to life. Over the past few years I've developed a habit of taking electronics things to bits, and - just occasionally - making them work again afterwards. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the launch of the HP-35. I felt it was time to lift the lid at last.

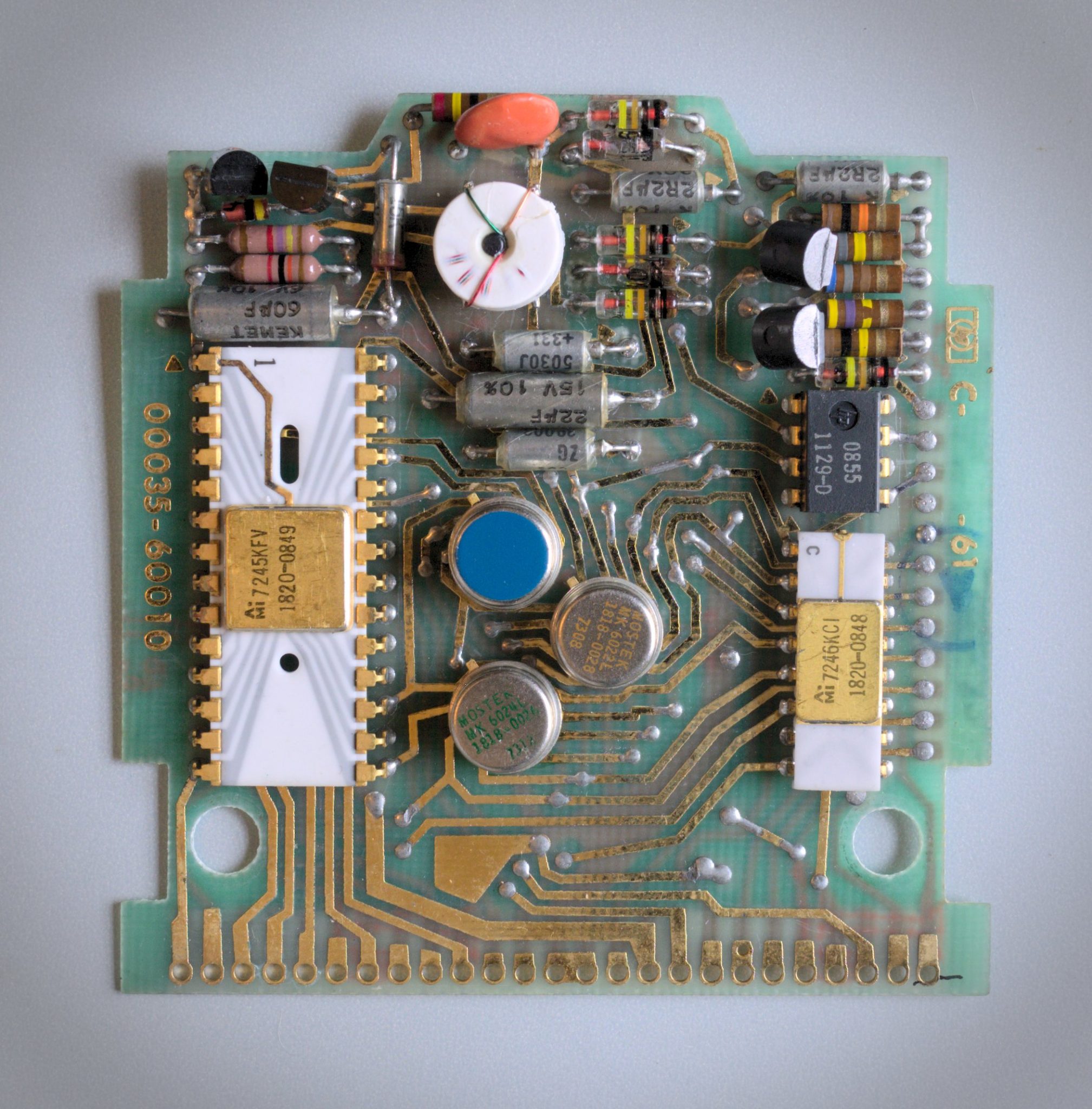

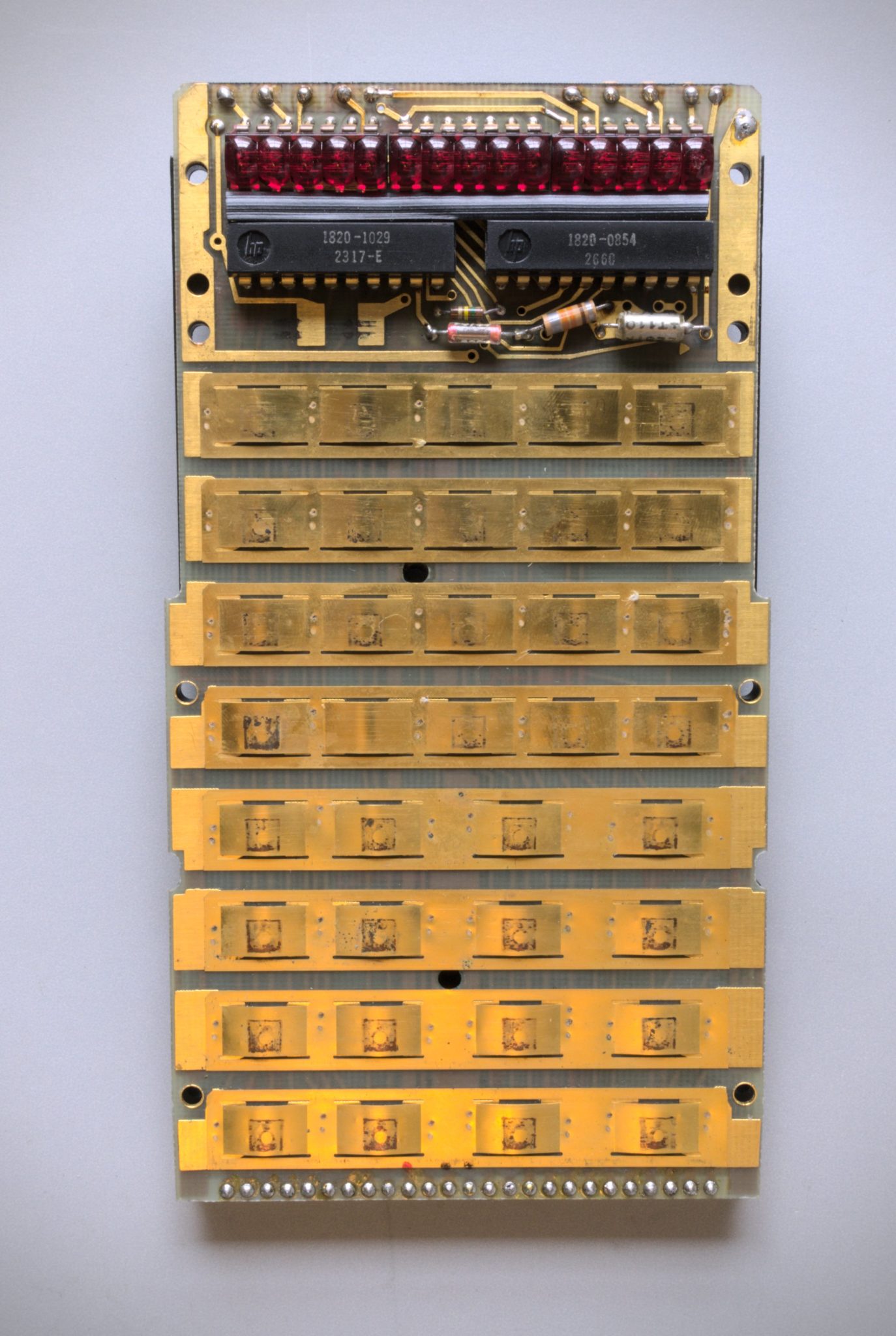

The first thing to observe is just how much gold is in this machine! HP's lab equipment was built to last, and designed to be repaired, and it's obvious they brought the same philosophy to the early calculators. By the 1980s, HP's calculators, while still high-quality, were definitely not repairable.

I've been puzzling over the fault for several weeks. The internal power supply is designed to generate three voltages: 6V, 8V and -12V. The first two were present but not the -12V. Some speculative replacement of parts made no improvement. Bear in mind that the componentry is 1970s vintage, but some of the obsolete parts can still be found by diligent search. Eventually, this week I turned my attention to a tiny transformer. You can see it encased in a cylinder of white goop at the top of that circuit board. I desoldered it, and as I pulled it out, it became obvious that one of the leads was broken, probably corroded by leaked battery contents. Resoldering that joint brought the calculator to life for the first time in 40 years or so.

There are still problems: the power switch doesn't work properly, and some keys don't register, so I've got more work to do. But it was a good feeling to see those tiny LEDs light up again.

Ironically, I bought another HP-35 on ebay, advertised as 'not working, for spares only' thinking it would be a good donor for parts. I simply made a makeshift battery pack for it and it worked immediately. It has the '2.02 bug'!

This project has thoroughly obsessed me for a couple of months. I watched a YouTube presentation by a man who has built his own HP-35 from first principles. He said something which sums up my autumn 2022.

I discovered a whole world of classic HP calculator enthusiasts on the web. First I thought they were lunatics, but I couldn't look away. Eventually I quietly became one of them.

The System, revisited

There was one more small pools win, more like a month's salary, than a year's, but then the government put up tax on football pools. My dad was smart enough to know that the small edge he enjoyed on the pools would be eaten up by this reduction in the pot, so he stopped playing. I think he went back to the horses for a while, then the lottery; you may think that is pure chance but dad had other ideas!

We had a second holiday at Butlins in the drought summer of 1976 and I remember the clouds bursting as we came home by coach in late August, the first rain for two months.

There were more calculators. After the HP-35, there was the Novus, then a Texas Instruments programmable SR-56, on which I did my first programming, a golf game as I recall, then the TI-58, with plug-in ROM modules. By this time home computers had arrived and dad brought home the Exidy Sorcerer, a machine with a massive 32kB of memory. "How could we ever fill it?" we said to ourselves. (I renovated that a couple of years ago.) On it went for the next thirty years or so.

He never kicked the habit. In total I inherited more than a dozen calculators including a couple more classic HP's. They are delightful things, and a lovely reminder of my dad, and his System.