There is little time for rest in war. Early in 1916 the battalion was sent to France, now to become part of the 16th (Irish) Division there. Soon Irish politics were to affect them. To understand why we need to go back a little in time.

In the Summer of 1914, the topic of conversation in political London was not Germany but the prospect of civil war in Ireland. The long campaign for Irish Home Rule had come to a head. Irish Nationalists were promised Home Rule by the Liberal Government. This was fiercely resisted by the Protestant Ascendency of the North, which had been effectively in charge, not only of Protestant Ulster but, also, of the Catholic South. They feared being dominated by those of a religion they regarded as alien.

Under the leadership of Carson the resistance became militant. “Ulster will fight and Ulster will be right”, was the slogan. Arms were acquired and training of a Volunteer Army began. In response, the Catholic Nationalists of the South began to raise a similar force of Volunteers.

Matters climaxed in 1914 with what became known as the Curragh Mutiny. The government in England showed signs that they were prepared to enforce Home Rule and put down any Protestant rising. Now, this was fiercely resented by many officers in the British Army in Ireland — not least by General Gough — many of whom were members of the Protestant Ascendency. They threatened to refuse orders and resign their commissions.

With the outbreak of war with Germany, matters subsided but did not go away. Among Nationalists of the South there was division. The Sinn Fein party saw England’s difficulty as Ireland’s opportunity. They conducted a vigorous campaign against the idea of Irishmen joining the British Army. The numerically larger Parliamentary Party, under John Redmond, took a different view. They were much more sympathetic about the immediate cause of the outbreak of war: the invasion of Belgium, a small nation, like themselves, by Germany. The Redmondites supported enlistment. Since enlistment was then voluntary, it must be supposed that soldiers of the RMF did not take the Sinn Fein view. This did not help them in the future since perception often counts for more than fact.

Just after the arrival of the 1RMF in France, there took place in Dublin The Easter Rising: rebellion against British Rule. To tell truth, it was a bit of a ragbag of a rebellion, organised, or rather disorganised by a mix of dreamers and activists. They took possession of the Dublin Post Office and a bakery and, really, not much more. The rebels were not popular with the inhabitants of Dublin, sometimes finding themselves spat upon by women, who might have men fighting at the front.

The British Army did not have too much difficulty putting down the revolt, bringing in superior force and gunships on the Liffey. Then they made an enormous mistake: they simply shot the ringleaders.

Suddenly, general Irish hostility to the rebels disappeared. They became, and have remained, Irish heroes. This was to have crucial importance in the later struggle for Irish Independence. The connection between events in Dublin and Gallipoli were clear to many Irishmen. The song ‘The Foggy Foggy Dew’ about the Easter Rising contains the lines:

Tis better to die ‘neath an Irish sky

Than at Suvla or Sedd-el Bahr.

The Rising had a more immediate effect on the 1st RMF. Within 48 hours, the Germans tried to turn it to propaganda advantage. They put up placards in the trenches opposite them. Under the heading ‘Brave Munster Fusiliers’, the Times reported that the Munsters responded by singing Irish songs and ‘Rule Britannia’. A raiding party, many of them said to be wounded, crawled across no-mans-land and seized the obnoxious placards carrying them back in triumph. The battalion war diary was less dramatic. A reconnaissance party had found the placards in an unoccupied German sap and brought them back. They said: “Irishmen! Heavy Uproar in Ireland: English guns are firing at your wives and children! 1st May 1916.”

Attitudes to the Munsters and other Irish regiments were changed by all this, however unfairly. There grew to be suspicion of their loyalty, particularly among the officer class. And among lower ranks: they could now be expected to be greeted with the taunt: “Here come the Sinn Feiners”

The battalion was lucky enough to be in reserve for that terrible day which launched the Battle of the Somme, but they were soon engaged in fighting, significantly alongside the largely Protestant 36th (Ulster) Division. In the Autumn they played a major part in the capture of Guillemont and Ginchy, two German strongpoints that had resisted attack after attack. The week of their capture was notable for fierce fighting in which perished Tom Kettle, Irish Nationalist Member of Parliament, writer friend of James Joyce and a character in many of Joyce’s works. He wrote a beautiful poem for his daughter the night before he was killed.

Know that we fools, now with the foolish dead,

Died not for the flag, nor King, nor Emperor,

But for a dream, born in a herdsman’s shed,

And for the secret Scripture of the poor.

Also killed that week was Raymond Asquith, writer son of the British Prime Minister, who also left memorable accounts of life in the trenches.

Also iconic for me is a photograph taken of soldiers of the 16th Division returning from that battle of Ginchy. Tiny details tell an unintended story. The groups of soldiers somehow have a jaunty look, though those nearest the camera carry on their shoulders a stretcher with a wounded soldier. They are passing a dead horse. You notice the hand of the wounded man, holding his forehead. You notice the schoolboy faces of some of the soldiers and that they pay no attention at all to the horse, it is clearly too ordinary a sight. And you notice that the horse, in its moment of deathly fear, has evacuated its bowels.

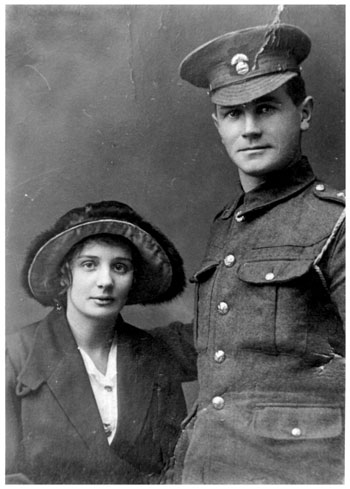

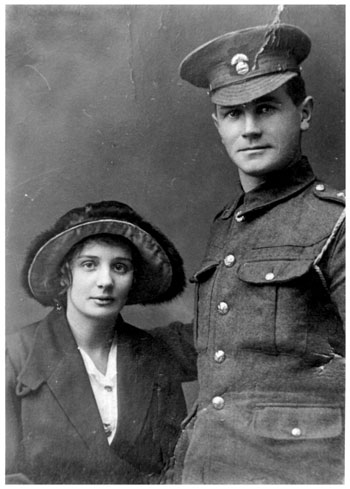

At Christmas, some relief for the Munsters. There is Leave. Bob Jordan returns to Coventry and he and Elsie Flemming are married. She has gathered together, in her own words, a few sticks of furniture for a home in a room above a shop in Far Gosford Street.

Back to the Front for the Year of Passchendaele. Again it is to be a story of great plans, with little success at great cost. The Haig doctrine of attrition, that ultimately we would be able to stand the casualties better than the Germans, was to be tried again. Soon, for once, the Munsters were about to be lucky in their general.

General Plumer could not have looked less like an effective general if he had tried. Think of an older version of the comic character ‘Mr Pastry’. The very image of a blimp. But his actions demonstrated complete professional efficiency. The target was to be the Messines Ridge. The battle plan was thoroughly thought out in meticulous detail and rehearsed over and over. Survival, not sacrifice, was part of the thinking and the confidence of the soldiers was won. In the event, in June, an enormous explosion in tunnels dug under the German lines opened the attack, which was completely successful, with low casualties.

Elation did not last. The Messines battle was only a prelude to the main campaign that was about to begin. For this, the 16th Division was to be part of General Gough’s 5th Army and this was unfortunate.

Gough was no impartial observer of Irish politics. In 1914, he had been a leading actor in the Curragh Incident. He had previously reported to the King’s Private Secretary:

The Nationalist Party would not be loyal. The idea of these disloyal men becoming our rulers was an outrage to very decent feeling I possessed — they would not give us clean government but, instead we would have corruption and graft and probably the country would be inundated with unscrupulous Irish American low class politicians — I could not tolerate the possibility of having a priest-ridden government.

These views would not be without future relevance.

As if timed to coincide with the opening of the attack on the Passchendaele Ridge, the rains came. It rained and it rained. It rained in cataracts such as no one could remember. The 16th were given targets on the Frezenburg Ridge. They had a long march to the battle, were thrown straight in and fought from zero hour till nightfall. But they were thrown back. The corps commander was full of praise for their performance but, yet, they were thrown back.

At first reports of the Great Battle were golden accounts of triumph. Misleading reports sent by Haig encouraged this belief. The Times reported: “Everywhere our objectives were obtained. — The beginning is splendid — The German front line broken … Casualties remarkably light.”

It was not true; it could hardly have been less true. As this became apparent, blame began to fly and the commanders concerned hastened to revise history. Haig seemed to blame his commanders for being in too much of a hurry and not following his suggestion of waiting for better weather. Gough found a more congenial scapegoat: blame the political unreliability of the 16th for inducing insufficient determination.

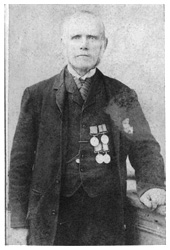

There is nothing new in Generals blaming their troops when things go wrong. I can’t help being reminded of an occasion six decades earlier, when John Jordan, then an eighteen-year-old, was flung with the rest of the 57th Regiment of Foot — the original ‘Diehards’ — against strong Russian defences at the Redan, Sevastopol. They were repulsed and there was criticism from Lord Raglan. An observant Colonel took a different view:

The men, I understand did not behave well. But this no doubt arose from mismanagement of the attack and is possibly a good lesson for some of our officers, who always think that British pluck has done and can do, everything. Now British pluck is not absolutely universal. When present it is as good as any pluck, and is in some respects better but without head is worth very little.

To me, Gough’s attitude seems like a case of: “my mind is made up; don’t confuse me with the facts.” For the record, the 16th lost 221 officers and 4064 men in the first 20 days of August. But a sort of whispering campaign against Irish soldiers had begun.

It would be tedious to detail the despondent soldiering of the British Army for the rest of 1917. This was the point at which there set in a kind of hopeless despair in the mud and blood of Passchendaele. Many died of drowning in the shell-holes. The Munsters, with the cold, wet, lice, and rats of Flanders might even have been nostalgic for the parched heat and flies of Gallipoli.

Meanwhile there took place an event that would have profound effects on the soldiers in 1918: The Russian Army collapsed and the October Revolution took Russia out of the War. This allowed the Germans to transfer something like 70 Divisions from the Eastern Front to the Western.

In December the 16th were moved East of Peronne, to what was reckoned a quiet sector.

As 1918 opened, the British High Command realised that the Germans would use the massive new forces for an attack aimed at ending the War before American troops arrived in numbers to change the balance of power, but GHQ misjudged where it would take place. Haig was more concerned about the northern part of the line because of the threat to the Channel Ports. Consequently, in the south, Gough’s 5th Army held 42 miles of front with fewer men than elsewhere. Brigades were reduced from 4 battalions to 3 and those understrength.

To cope with the lack of men, a new theory of war was borrowed from the Germans: Defence in Depth. The Germans had had years to implement the method; the British had only a few weeks.

Briefly, the system relied, since there were insufficient men to man trenches — defence in breadth — on separated strong points, from which cross firing machine guns would destroy attacking troops. Beyond that there would be troops in a battle zones to deal with any breakthrough, and reserves further back.

It may have been a good system, given time, but in practice, projected strong points that appeared on maps did not always exist in reality. Whether the Germans realised how weakly held was this section of the Front is not clear, but it was here that the Germans massed.

As the winter passed, Gough began to be alarmed at signs of activity in front of 5th Army but his concerns were dismissed by GHQ, who said it “was unlikely to be the scene of serious hostile attack.” Gough, in turn, resisted requests from 16th Division officers on the spot for changes to meet the inadequacies. They wanted reserves further forward. Gough refused, saying: “The Germans are not going to break my line.”, a response received with pessimism by the 16th.

The huge assault, which became known as the Kaiserschlacht, was launched on 21st March and aimed with some precision at the point where the 16th were placed. Four weak battalions faced a dozen times as many German battalions.

At 4.30 in the morning, 6000 German guns delivered the heaviest bombardment of the war. With the explosive shells were mixed gas shells: chlorine, mustard, tear gas. The earth trembled with the force of it all.

The total confusion that followed was assisted by heavy fog. Trenches collapsed, wire and strong points flattened. Infantry groped about in gas masks. Horses panicked. Command and control virtually ceased to exist as communication cables were broken by the shellfire. The defenders were deaf, dumb and blind.

When the German Infantry assault began, they found it easy, hidden by the fog, to infiltrate between and surround the strong points and destroy with grenades. Behind them, through the gaps, followed hordes of Germans. Units in the so-called battle zone found themselves cut off and surrounded.

The 1st RMF were lucky that day: they were some way back in Reserve, with 6th Connaught Rangers. A knee jerk order for a counter attack was given. It was a useless, suicidal gesture. Someone at HQ must have realised this for the order was cancelled. The Munsters got the second order in time; the Rangers did not. The result for them was a tragic episode of useless valour.

At GHQ it was thought that the Germans would halt to re-organise the next day. They did not; they swept forward. Many units found themselves cut off and surrounded. Some fought till the ammunition ran out and then were forced to surrender. The Munsters were among those cut off. The Great Retreat had begun.

On the 23rd, Gough ordered retirement behind the Somme and the remaining decimated battalions of the 16th slipped away. They were mixed with vast columns of French civilians, fleeing with whatever possessions they could manage.

Confusion everywhere. The destruction of the Somme bridges was ordered. Mixed groups from different units organised a fighting retreat from behind German lines as best they could. A mixed group of 1st RMF and 6th Rangers, under the command of Lt. Col Feilding, gathered stragglers from other units. They tried several bridges across the Somme without success. Finally they got across by rushing the guards on a bridge occupied by Germans.

With others, they were gathered for hastily organised defence before Amiens. It held and counter attacks began. Feilding was wounded and Guy Nightingale, now a Major, assumed command.

Despite the disorganisation and confusion, the Amiens line held and Foch was put in overall command at a hurried conference of High Command in Doullens. The Germans failed in their attack on 30th March.

After the Retreat, the inevitable blame game began. Gough was sacked. Haig did defend him on grounds of lack of adequate resources but this reason would have reflected badly on the government itself, so it was ignored. The 16th also came in for criticism for lack of determination, not least from Haig. There seems to have been no evidence other than prejudice for this and it flew in the face of German accounts. Nightingale is furious about the criticism:

We owe it all to the Sinn Fein trouble. An Irish division or regiment is mud out here or anywhere and however fine it did there would be all sorts of nasty rumours.

Later he wrote:

I’m glad I’m an Englishman in an Irish regiment, as I can go unprejudiced to those outside fellows and tell them straight that though I’m not an Irishman I would sooner be in an Irish regiment with Irish soldiers behind me in a scrap than any English or Scotch troops they would like to produce.

Nevertheless, what little was left of the 16th Division was disbanded and the remains sent to other Divisions. 1RMF went to 57th Division.

Somewhere in all that confusion Peter Jordan was wounded and he died of wounds on 30th May. The adjoining graves to his are those of a group of Canadians who were killed in a German bombing of a hospital at Doullens that same day. Whether Peter’s death was part of the same incident, I do not know.

The Kaiserschlacht was the Germans last serious throw. They had advanced more than any time since Mons, yet a little mysteriously they were on the verge of collapse. Part may be psychology. Even before March 21st, there were some signs of low morale among the Germans. Even during their advance, there were signs of indiscipline, many getting drunk on French wines and enjoying the stores they found, instead of pressing home the attack on Amiens. For some, knowing of their families close to starvation at home, the relative plenty of the Allies may have created something like hopeless despair. Add to that the prospect of the arrival of unlimited American soldiers and their victory may have had a touch of hollowness.

Twice more, the Germans attacked and failed. In August they were attacked, in turn, in what came to be called the black day of the German Army. From now on they are in general retreat.

The 1st RMF, with the 57th Division are with the first group to break through the Hindenburg Line

Nightingale records it all. Still protesting about the bad treatment of Irish regiments, he also records the steady forward movement:

The Boche is evidently very worried and doesn’t know where he is. He is shelling very unmethodically and mostly with big guns further back than usual… Gerry is gassing us at present, but so wildly and vaguely that it can do no harm.

In September, the crumbling morale of the Germans evidenced by extremely cooperative prisoners: “The prisoners we took this morning said that they were flogged on to the attack last night and ended by shooting their officer.”

But danger is not behind them. Nightingale takes command again when the CO is killed. A much-reduced battalion of 7 officers and 261 men.

By mid-October, they were outside Lille and soon after entered the town as Liberators:

This morning we walked into a city with 125,000 civilians still there, mostly women and all in a high state of excitement! I laughed till I nearly fell off my horse. It was a bit early in the morning and they were not expecting to see any troops, but they were brought from their beds by the sound of our band playing O’Brien Bourru and the Marseillaise! They were laughing and screaming and crying and flinging themselves round the necks of the men and I was very glad that I was on my horse and even then was nearly pulled off several times.

Somehow that recalls the moment they left Coventry, nearly 4 years before. And somehow, after that, all is anti-climax. The Munsters ended the War in Lille and formed the Guard of Honour there for the French President. One of those present for the celebration was Winston Churchill; now back in the Government, as Minister of Munitions.

I have a sort of imagined picture of Nightingale and my father and the very few of those that left Coventry looking at each other emotionally and emotionless.

Kipling has described beautifully the peculiar psychological confusion of the moment when the Armistice was signed on the 11th hour of the11th day of the 11th month:

Men took the news according to their natures. Indurated pessimists, after proving it was a lie, said it would be just an interlude. Others retired into themselves as if they had been shot, or went stiffly about the meticulous execution of some trumpery detail of kit-cleaning. Some turned around and fell asleep then and there; and a few lost all holds for a while. It was the appalling new silence of things that soothed and unsettled them in turn. They did not realise until all sounds of their trade ceased, and the stillness stung their ears as soda water stings the palate, how entirely these had been part of their strained bodies and souls. It felt like falling through into nothing. Listening for what wasn’t there and trying not to shout when you remembered for why.

Nightingale’s account is somehow much more downbeat, almost depressed:

I expect you had a great time when the Armistice was signed. We had a very quiet time. We were in Lille and heard about it at about 9 a.m. Nothing happened. We had parades till 12.30 as usual… There was no excitement in the place we were in… I believe they rang the bells at some of the big churches in Lille, but that was all. Since then we’ve been training harder than ever and have had several inspections by Generals.

The rest is epilogue. With Irish Independence, the Royal Munster Fusiliers were disbanded in 1922. Guy Geddes was one of the small group handing over the Colours at the ceremony at Windsor.

Bob Jordan returned to Coventry, got drunk at the Victory Celebrations and had to be helped home. For the next 27 years, he and Elsie applied themselves to the difficult but more congenial work of raising a family in the harsh economies of the Twenties and Thirties. They lost their eldest son in the Second World War.

Bob Jordan returned to Coventry, got drunk at the Victory Celebrations and had to be helped home. For the next 27 years, he and Elsie applied themselves to the difficult but more congenial work of raising a family in the harsh economies of the Twenties and Thirties. They lost their eldest son in the Second World War.

There is a curious little incident, which stays in my mind, at the end of that WW2. In the general election of 1945 Winston Churchill came to Coventry, electioneering. He was naturally then at the height of popularity and everyone wanted to see him. Except my father, who said very firmly: “I wouldn’t cross the road to see him.” He was the least political of men and, as a 14-year-old boy, I took this in with silent incomprehension. I did not then know about Gallipoli. Within a month or so Churchill had been defeated by Clement Attlee, one of those who fought at Gallipoli. A few days after that my father died suddenly and, a few days later, the atom bomb was dropped and another War was over.

Guy Nightingale seems to have found difficulty in adapting to Peace. He was still in his twenties and had no experience since school except soldiering. He did bits of soldiering about the world, then retired to Somerset as a half-pay Major. He died at the age of 43, in 1935. There are differing accounts of his death. One, dramatically, says he killed himself with his own service revolver on the twentieth anniversary of the Landing on V Beach. A second obituary suggests a long illness, bravely endured. The death certificate is more prosaic. It gives three causes: cardiac syncope; delirium tremens and chronic alcoholism. “‘What is Truth?’, said Jesting Pilate, and would not stay for an answer.”

The casualties of war do not all take place on the battlefield. Let the last word go to Maude Nightingale, Guy’s mother. Writing from a Nursing Home in Newbury in 1947 to the former chaplain of the Munsters, she writes:

The mishandling of the RMF broke my Guy’s heart — I am glad you saw Guy’s grave — I shall never cease to miss him. I am 83 now so it will not be long before I see him. I have no family left in England: my daughter, grandchildren and great grandchildren are scattered all over the Empire.

Perhaps not quite the last word. Let that go to the Irish poet, Tom Kettle, who was killed, on the Somme, at Ginchy:

I have seen war and faced Artillery and I know what an outrage it is against simple men.

Bob Jordan returned to Coventry, got drunk at the Victory Celebrations and had to be helped home. For the next 27 years, he and Elsie applied themselves to the difficult but more congenial work of raising a family in the harsh economies of the Twenties and Thirties. They lost their eldest son in the Second World War.

Bob Jordan returned to Coventry, got drunk at the Victory Celebrations and had to be helped home. For the next 27 years, he and Elsie applied themselves to the difficult but more congenial work of raising a family in the harsh economies of the Twenties and Thirties. They lost their eldest son in the Second World War.