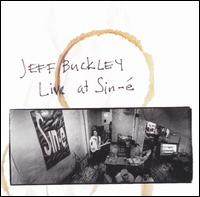

So I was listening today to Jeff Buckley – Live at Sin-é and he took me off on a little ethno-musicologist wandering. If you don’t know it, this is an extended recording of one of Jeff’s solo shows at a tiny NYC club, made shortly before he signed to CBS to record Grace (recently voted #61 in Channel 4’s 100 greatest albums). So in a way it marks the end of innocence for Jeff, and the start of an arc that would see him achieve superstardom and tragically drown within four years.

So I was listening today to Jeff Buckley – Live at Sin-é and he took me off on a little ethno-musicologist wandering. If you don’t know it, this is an extended recording of one of Jeff’s solo shows at a tiny NYC club, made shortly before he signed to CBS to record Grace (recently voted #61 in Channel 4’s 100 greatest albums). So in a way it marks the end of innocence for Jeff, and the start of an arc that would see him achieve superstardom and tragically drown within four years.

It’s fantastically discursive. There’s little or no editing, and so all of the between-song patter is there on CD, and in Jeff’s case this means snatches of nigh-perfect renditions of radio jingles, Zeppelin, Doors and Dylan. He has clearly absorbed all of this material through obsessive study and practice, and he uses snippets as a kind of extended vocabulary, just as a poetry-maven might slip in quotations to illustrate a debate. At one point he performs a song by the great Pakistani Qawwali singer, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, and it’s hard to tell whether he has learned the song phonetically, or studied the original Sufi poetry — but you suspect it might be the latter. He does mention that he knows “everything” about Nusrat, including his boyhood nickname.

However it was not the Nusrat song that caught my ear. There’s a track callled Dink’s Song, a long impassioned blues narrative that is classic Jeff. Based on stanzas that you’ve heard spun through Robert Johnson, Son House and about every other Delta bluesman, but driven towards the type of climax that Steve Berkowitz, Jeff’s A&R man, called “the flying Buckleys”. I’m pretty blues-literate but I’d never heard of this Dink’s Song so I googled it.

Roger McGuinn’s folk den provided the answer. John Lomax collected the song on a field trip to College Station, Texas in 1908. He witnessed there what can only be described as a mating ritual among the black workers, slaves in all but the narrowest definition. Lomax’s description from his 1947 book, Adventures Of A Ballad Hunter:

I found Dink washing her man’s clothes outside their tent on the bank of the Brazos River in Texas. Many other similar tents stood around. The black men and women they sheltered belonged to a levee-building outfit from the Mississippi River Delta, the women having been shipped from Memphis along with the mules and the iron scrapers, while the men, all skilful levee-builders, came from Vicksburg. A white foreman volunteered: ‘Without women of their own, these levee Negroes would have been all over the bottoms every night hunting for women. That would mean trouble, serious trouble. Negroes can’t work when sliced up with razors.’

The two groups of men and women had never seen each other until they met on the river bank in Texas where the white levee contractor gave them the opportunity presented to Adam and Eve – they were left alone to mate after looking each other over. While her man built the levee, each woman kept his tent, toted the water, cut the firewood, cooked, washed his clothes and warmed his bed. Down on the dumps nearer the river, clouds of drifting dust swirled from the feet of moving mules and from piles of shifted earth, while the shouts of the muleskinners sometimes grouped themselves into long-drawn-out couplets with a semi-tune – levee camp hollers.

But Dink, reputedly the best singer in the camp, would give me no songs. ‘Today ain’t my singin’ day,’ she would reply to my urging. Finally, a bottle of gin, bought at a nearby plantation commissary, loosed her muse. The bottle of liquor soon disappeared. She sang, as she scrubbed her man’s dirty clothes, the pathetic story of a woman deserted by her lover when she needs him most – a very old story. Dink ended the refrain with a subdued cry of despair and longing – the sobbing of a woman deserted by her man.

If I had wings like Noah’s dove

I’d fly up the river to the one I love

Fare thee well, oh honey, fare thee well

I’ve got a man, he’s long and tall

Moves his body like a cannon ball

Fare thee well, oh honey, fare thee well

One of these days and it won’t be long

Call my name and I’ll be gone

Fare thee well, oh honey, fare thee well

I remember one night, a drizzling rain

Round my heart I felt a pain

Fare thee well, oh honey, fare thee well

When I wore my apron low

Couldn’t keep you from my do’

Fare thee well, oh honey, fare thee well

Now I wear my apron high

Scarcely ever see you passing by

Fare thee well, oh honey, fare thee well

Now my apron’s up to my chin

You pass my door and you won’t come in

Fare thee well, oh honey, fare thee well

If I had listened to what my mama said

I’d be at home in my mama’s bed

Fare thee well, oh honey, fare thee well

So it’s the classic tale of woman left barefoot and pregnant by a deserting philanderer, cf Willie O’Winsbury in the Scottish tradition.

But back to Jeff. Closer inspection reveals that he has sacrificed form for feeling. He has attempted a sex-change on the lyric, that renders it almost nonsensical:

if I met your man, and he was long and tall

I’d heave his body like a cannonball

fare thee well, my honey, fare thee well

Furthermore he has injected bastardised versions of well-known stanzas, like Robert Johnson’s Come On In My Kitchen, which he renders thus:

oh she’s gone

I know she won’t come back

oh she took the last nickel out of my saving sack

In Johnson’s original “I took the last nickel out of her nation sack”… a nation sack, I discovered, is a bag used specifically by women to carry their mojo, or voodoo charm, a talisman used for spells of female domination over men. One wonders whether Jeff’s aware that a man would never use a nation sack, and hence changed to “saving sack”, or is it just a slip.

Ultimately one’s left with the impression that Buckley didn’t take too much care with the lyric and just let rip with his stream of consciousness. This would be typical of his approach, I think, and I don’t have a problem with that. His spirit and musicality do it for me.

And what of Dink’ She was dead when Lomax returned for a second visit a year later. And it would be twenty-five more years before Lomax and his son Alan returned with some extrememly primitive portable recording equipment to capture the sound of the blues. I’d love to hear Dink’s own rendition of her song, and so, I suspect, would have Jeff.

PostScript: Thanks to Brandon and Annalivia for the great comments. I’m a little shame-faced that I didn’t know about the Dylan version; almost certainly the model for Buckley’s. Of course, Dylan’s is now in legal circulation, thanks to the No Direction Home soundtrack, and I must do a little comparison to see how the two match up. And now we have a few candidates for Dylan’s source: Van Ronk, Baez, and also Pete Seeger who, I discover, recorded it in the late fifties as part of a massive project called America’s Favourite Ballads. Thanks to Scorsese’s film, Dylan’s early New York period is buzzing in my head. I dug out Chronicles Vol. 1, the kind Christmas gift of father-in-law Peter and am busily reading it. Another discovery, the woman whom Dylan describes as his favourite blues singer of the Greenwich Village era, Karen Dalton. She has a couple of albums in circulation and I’m looking forward to hearing them too.

By the way, the Seeger album is available on emusic.com, my absolute favourite legal download site, and a bargain at US$10 for 40 tracks a month. They have a wonderful archive of independent music, and I intend to write a jordan-maynard.org piece about it one of these days.

After the customary pause for procrastination, a small set of photos from this year’s Glastonbury festival are now posted in the

After the customary pause for procrastination, a small set of photos from this year’s Glastonbury festival are now posted in the

So I was listening today to Jeff Buckley – Live at Sin-é and he took me off on a little ethno-musicologist wandering. If you don’t know it, this is an extended recording of one of Jeff’s solo shows at a tiny NYC club, made shortly before he signed to CBS to record Grace (recently voted #61 in Channel 4’s 100 greatest albums). So in a way it marks the end of innocence for Jeff, and the start of an arc that would see him achieve superstardom and tragically drown within four years.

So I was listening today to Jeff Buckley – Live at Sin-é and he took me off on a little ethno-musicologist wandering. If you don’t know it, this is an extended recording of one of Jeff’s solo shows at a tiny NYC club, made shortly before he signed to CBS to record Grace (recently voted #61 in Channel 4’s 100 greatest albums). So in a way it marks the end of innocence for Jeff, and the start of an arc that would see him achieve superstardom and tragically drown within four years. “A record made from nothing but other records'” writes Frank Broughton on his djhistory.com site. The innovations that this record introduced have become so commonplace that it almost sounds clichéd: the Good Times riff, the scratching and ‘found’ recordings. But try to imagine this crackling from the speakers in 1981. This is where it started baby-boy!

“A record made from nothing but other records'” writes Frank Broughton on his djhistory.com site. The innovations that this record introduced have become so commonplace that it almost sounds clichéd: the Good Times riff, the scratching and ‘found’ recordings. But try to imagine this crackling from the speakers in 1981. This is where it started baby-boy!